Read the first three paragraphs of Pericles’s speech and consider the way he frames the introduction. How does he introduce his major ideas? How effective is the introduction?

Pericles opens with a recount of history. He says he finds the funeral oration custom silly because the dead’s actions speak for themselves, and most people will disagree on how much merit to attribute to them anyways (too much or too little), but obliges to fulfill his responsibility nonetheless. He then celebrates the preceding generation’s actions during the Greco-Persian wars, which creates a tether between that heroic conflict and what the Athenians are experiencing during the current Peloponnesian one. He ends his introduction by suggesting how the current state of affairs—the way of life Athenians live—is what the dead are defending, and needs to be mentioned in the same breath as the bravery of the fallen.

The effect of this intro is to give Athenians a sense of legacy and make them feel like they’ve inherited their current conflict, rather than brought it about themselves. The heroism of their fathers shames the current generation into courage, and the historical events that birthed the Athenian empire make it natural to think that it must be defended. Pericles initiates a portrayal of the core values of the Athenians—a theme he will expand on—as incompatible with those of their enemies and as an integral part of their conflict (rather than mere imperialist ambition).

The only thing I don’t understand is the opening disclaimer; it seems as if Pericles is providing a defense for himself. But I also sense a subtle compliment for the inadequacy of rhetoric to celebrate military sacrifice. (Perhaps that’s an affectation of humility before our statesmen assaults us with his famous speech?)

Why does Pericles spend so much time praising Athens, its form of government, and its culture? What does this suggest about his real motives in making this speech?

Things are looking down. War has just started and here is the first batch of young dead men that will surely be followed by more. Pericles isn’t just giving a eulogy: he is justifying these corpses to the citizens of his city, and to their family members. He needs to keep people’s spirits up and resilient for more conflict. He also wants to inspire the other soldiers who see the recent dead as prophesies of their own fate.

Beyond this, Pericles probably does believe in the merits of Athens and her people, so this praise could also be genuine admiration that everyone should participate in. For what it’s worth, I agree with Pericles that the Athenian life was more realized than the Spartan one (if you’re male, that is).

What difference does Pericles see between the way Athens prepares for war and the way its neighbors do? Why is this difference important to the speech?

Sparta was a militarized state: its citizens prepared for war all year round. Athenians were mostly a volunteer army. This naturally made the former more intimidating (and potent) warriors, but the Athenians did surprisingly well against them, and their fears were partly psychological rather than real.

Pericles wants to instill a sense of pride in this seeming disadvantage by pointing out how the Athenians are still brave and powerful while being more well-rounded human beings. The unidimensional lives that Spartans live do not even make them superior to the Athenians on the battlefield. This multifaceted dimension of the Athens is portrayed as a virtue that guards against their fears of Spartan prowess.

Pericles tries throughout his speech to increase the hostility of his audience towards Sparta. Why?

Interestingly, Pericles rose to power through an Anti-Spartan political party, opposing the prior pro-Spartan one. So this demonizing isn’t just to rally people by dehumanizing the enemy, it’s also to reinforce his legitimacy as the leading statesmen of the day.

How does Pericles distinguish himself from “long winded orators”? Why does he say so little about the men whose funeral he is speaking at?

Pericles wants to avoid repeating well-worn material. He (ostensibly) does not need to remind his people that enemies are bad. What he does want to do is elevate the civic spirit to something above and beyond mere survival: that Athens is a “city on a hill” which is worth defending beyond the simple fact that it’s their home. This is why he spends so little time dwelling on the individuals who have died. They didn’t die just defending a city, they are the city, in the sense that their values are what imbue Athens with such wonder and prestige. This stressing of values raises the concern from the mere material, to the transcendent.

I think of a similar tactic during Cold War rhetoric. Both the US and the Soviets defended their empires by praising their respective ideologies. To each it was more than just land at stake: it was an entire conception of living. Pericles here does the same.

What advice does Pericles give to women? Might anything in this passage confirm Plato’s argument that it was Aspasia, a woman, who wrote the oration for Pericles to give? Explain.

Pericles tells women the best thing they can do is not get noticed, for better or for worst. This is such an outrageously sexist statement that one is right to suspect that Aspasia may have been on Pericles mind. While it’s true Athens was extremely sexist, given what we know about Aspasia’s influence of Pericles (he was mocked for listening to her so often), I suspect Pericles added this bit so to refute accusations that she crafted most—or all—of this now famous oration.

Cellar Door

Wednesday, July 18, 2018

Friday, July 13, 2018

My Thoughs on "Pacifism and the War", by George Orwell

What kind of case is Orwell making? Does he perceive his audience as supportive, hostile, lacking in information, partially supportive, or unconvinced about the importance of the issue?

Orwell opens with a syllogism that equates pacifism to pro-fascism. Beyond stating the transparent, he attacks the motivations of his opponents and recounts personal experiences to not only add credit to his views, but highlight the cloistered lives his opponents live (Orwell beats this drum a few times). He finishes by defending himself and providing his motivations, which are nobler than his moralistic opponents.

I don’t get a good sense of how Orwell views his audience, other than by treating them like adults. He attacks the pacifists’ arguments directly and does not seem to be pandering to any particular group. He does take certain values for granted: fascism is bad and must be resisted. Outside of that his tone is respectful, but firm.

What does Orwell mean when he says that during World War II pacifism was “objectively pro-Fascist”? From what you know about this conflict, judge whether it would have been possible to oppose the use of force by one side (the Allies) without supporting the ideology of the other side (the Axis).

He points out that if you hamper the efforts of the anti-fascist side, you de facto aid the pro-fascist side. I think this is right. The Axis powers killed innocent people who were passive, let alone passively resisting. Any arguments to the contrary are being willfully blind.

Why, according to Orwell, was pacifism not permitted in Germany and Japan during World War II?

As militant, fascist powers, pacifism is antithetical to their entire ideology.

What is the basis of Orwell’s distinction between “‘moral force’” and “physical force”? Which does he see as more desirable in World War II?

I interpret this to be recognition that moral compulsion does not have the same heft as the physical kind: one can simply ignore the former, but not the latter. This is especially true of fascist governments who make no pretense to being moral at all. In a war, such as WWII, it’s clear material force is what can win the day. Not moral posturing.

What arguments does Orwell characterize as “peace propaganda”? How is this related to “war propaganda”? What kinds of arguments might he see as the cornerstone of all kinds of propaganda?

Related to his earlier point, if pacifism is effectively pro-fascist, then by extension propaganda for peace creates the same effect as propaganda for war (just for the other side). Orwell is articulating what today might be called “dog whistle” rhetoric: his opponents defend their arguments as promoting peace, but actually only speak to those people who would prefer that the Axis powers succeed. As for what Orwell considers the basis of all propaganda, I cannot improve on this statement:

“…it concentrates on putting forward a “case,” obscuring the opponent’s point of view and avoiding awkward questions.”

What mistaken notions about fascism does Orwell attribute to the peace movement?

He lists five points that I won’t parrot here, but in essence pacifists obscure the lines between fascist and non-fascist so as to undermine the ethical imperative of the conflict.

Against what personal attacks does Orwell defend himself? Are his defenses necessary? Are they effective?

Orwell is accused of working for fascists, being part of fascist groups, and delivering propaganda for the British to India. These are strange accusations because they accuse Orwell of participating in, or sympathizing with, the very ideology he is calling to (militarily) resist. I’m not sure if his defending himself is necessary, but it sure doesn’t hurt. And for that matter I do think they’re effective: he easily disarms accusations of his sympathies and observes that his opponents are really not familiar with his work. The only area where I think Orwell is on thin ground is his writing for Adelphi. While writing for a vegetarian newspaper doesn’t make you a vegetarian, it does make you look chummy with them. (Unless of course Orwell was writing against the newspaper from within it, but he would have mentioned that if he had.)

Orwell opens with a syllogism that equates pacifism to pro-fascism. Beyond stating the transparent, he attacks the motivations of his opponents and recounts personal experiences to not only add credit to his views, but highlight the cloistered lives his opponents live (Orwell beats this drum a few times). He finishes by defending himself and providing his motivations, which are nobler than his moralistic opponents.

I don’t get a good sense of how Orwell views his audience, other than by treating them like adults. He attacks the pacifists’ arguments directly and does not seem to be pandering to any particular group. He does take certain values for granted: fascism is bad and must be resisted. Outside of that his tone is respectful, but firm.

What does Orwell mean when he says that during World War II pacifism was “objectively pro-Fascist”? From what you know about this conflict, judge whether it would have been possible to oppose the use of force by one side (the Allies) without supporting the ideology of the other side (the Axis).

He points out that if you hamper the efforts of the anti-fascist side, you de facto aid the pro-fascist side. I think this is right. The Axis powers killed innocent people who were passive, let alone passively resisting. Any arguments to the contrary are being willfully blind.

Why, according to Orwell, was pacifism not permitted in Germany and Japan during World War II?

As militant, fascist powers, pacifism is antithetical to their entire ideology.

What is the basis of Orwell’s distinction between “‘moral force’” and “physical force”? Which does he see as more desirable in World War II?

I interpret this to be recognition that moral compulsion does not have the same heft as the physical kind: one can simply ignore the former, but not the latter. This is especially true of fascist governments who make no pretense to being moral at all. In a war, such as WWII, it’s clear material force is what can win the day. Not moral posturing.

What arguments does Orwell characterize as “peace propaganda”? How is this related to “war propaganda”? What kinds of arguments might he see as the cornerstone of all kinds of propaganda?

Related to his earlier point, if pacifism is effectively pro-fascist, then by extension propaganda for peace creates the same effect as propaganda for war (just for the other side). Orwell is articulating what today might be called “dog whistle” rhetoric: his opponents defend their arguments as promoting peace, but actually only speak to those people who would prefer that the Axis powers succeed. As for what Orwell considers the basis of all propaganda, I cannot improve on this statement:

“…it concentrates on putting forward a “case,” obscuring the opponent’s point of view and avoiding awkward questions.”

What mistaken notions about fascism does Orwell attribute to the peace movement?

He lists five points that I won’t parrot here, but in essence pacifists obscure the lines between fascist and non-fascist so as to undermine the ethical imperative of the conflict.

Against what personal attacks does Orwell defend himself? Are his defenses necessary? Are they effective?

Orwell is accused of working for fascists, being part of fascist groups, and delivering propaganda for the British to India. These are strange accusations because they accuse Orwell of participating in, or sympathizing with, the very ideology he is calling to (militarily) resist. I’m not sure if his defending himself is necessary, but it sure doesn’t hurt. And for that matter I do think they’re effective: he easily disarms accusations of his sympathies and observes that his opponents are really not familiar with his work. The only area where I think Orwell is on thin ground is his writing for Adelphi. While writing for a vegetarian newspaper doesn’t make you a vegetarian, it does make you look chummy with them. (Unless of course Orwell was writing against the newspaper from within it, but he would have mentioned that if he had.)

Tuesday, January 26, 2016

Evening Song

To stroll in twilight hours, with feet adrift,

Is to dilute your soul, with mind to sift

The petty shame that would pollute your day

If left to fester there, and have its way.

Dismiss those thoughts; look up! The dangling dark

Just glistens there, as you pursue its arc.

Beyond a dying sun that rends the sky

Soft onyx waves pound out their lullaby.

Sweet dusk. You watch the dark as it cascades,

As shadows grow, as your existence fades.

Past streetlight beams and winking stars you find

The night that fell upon your state of mind.

It's not a sad, or glad, impression left,

But simply calm, through a nocturnal theft

Of sunlight's fears and hopes, which dusk ascends:

We but begin our lives when daytime ends.

Is to dilute your soul, with mind to sift

The petty shame that would pollute your day

If left to fester there, and have its way.

Dismiss those thoughts; look up! The dangling dark

Just glistens there, as you pursue its arc.

Beyond a dying sun that rends the sky

Soft onyx waves pound out their lullaby.

Sweet dusk. You watch the dark as it cascades,

As shadows grow, as your existence fades.

Past streetlight beams and winking stars you find

The night that fell upon your state of mind.

It's not a sad, or glad, impression left,

But simply calm, through a nocturnal theft

Of sunlight's fears and hopes, which dusk ascends:

We but begin our lives when daytime ends.

Thursday, November 19, 2015

Morning Song

Our lazy sun will never see me dream,

Just as no songbird will catch my worm.

Cold mornings find an ardent man agleam:

Bed made, tea poured, his ‘carpe diem’ firm.

Before daybreak all colors are converged

In twilight’s ebbing shade and flowing light.

I catch myself oft standing there submerged;

Engaged in plain, primordial delight.

Look out the window pane, see through the mist:

Old trembling trees; receding stars; loud crows.

As if the rest of it did not exist.

But then I spy—far off—a private rose.

In morning dusk, concealed by ashen hour

I claim the bashful, blooming flower.

Just as no songbird will catch my worm.

Cold mornings find an ardent man agleam:

Bed made, tea poured, his ‘carpe diem’ firm.

Before daybreak all colors are converged

In twilight’s ebbing shade and flowing light.

I catch myself oft standing there submerged;

Engaged in plain, primordial delight.

Look out the window pane, see through the mist:

Old trembling trees; receding stars; loud crows.

As if the rest of it did not exist.

But then I spy—far off—a private rose.

In morning dusk, concealed by ashen hour

I claim the bashful, blooming flower.

Tuesday, June 9, 2015

Hsun Tzu: Encouraging Learning

I ended up liking Hsun Tzu quite a bit, and am sad to see he doesn’t receive as much recognition as Mencius for developing early Confucianism. But many of his teachings did indeed become fundamental to the philosophy/religion, particularly his views on education. In his work Encouraging Learning, Hsun Tzu argued for the merits of life-time study, and suggested a school curriculum for all aristocratic children. Let’s examine a bit:

1.) What distinction does Hsun Tzu draw between “thought” and “study”? Why does he privilege study over thought in education? How have your teachers emphasized “study” and “thought” differently as you have progressed through school?

The philosopher noticed that he learned far more studying others than he did in isolated contemplation. This is probably an attack on loner intellectuals who became sages by sitting alone and studying the Tao (*COUGH Siddhartha COUGH*), but he also believes it’s simply more effective. We become great by studying great men, not mentally masturbating. Ignoring the patronizing third question I’ll instead retort by positing that a mix of contemplation and study is ideal. You need to first not assume these men are great by default, and review them before you study. And after you study you must expand or improve on what you’ve learned to take it to the next step.

2.) How would you classify Hsun Tzu’s methods of supporting his argument? What kinds of support does he include? What kinds does he omit? How persuasive are his methods?

It’s essay writing, with logical points consistently supporting his thesis. He uses analogies (usually 3-5 at a time) to drive an idea home. He quotes sacred texts, history, and great men. He also repeats his thesis throughout. With the exception of appealing to authority, I find his claims very convincing and favor his style over all other ancient Chinese philosophers.

3.) Several of Hsun Tzu’s metaphors suggest that hard work and study, rather than natural ability, determine success. How is this assertion important to the overall argument? Do you agree with his assessment? Why or why not?

It gives both hope and motivation to his audience. Just because we’re fat lazy slobs doesn’t mean we can’t change, and through study and industry we too can become gentle-sages. I agree deeply, and feel it has become common knowledge today. I mean, there are still missing elements, but the core argument is on point. Widespread education has systematically improved the living standards of every person, society, and state. But even facts aside, I know from my own personal experience that burning Friday-night oil reading this crap has made me happier and a better person.

4.) According to Hsun Tzu, what should be part of the education of a gentleman? What, by implication, should not be part of such an education?

Basically studying laws, classical poetry, history, classical music, and the sages’ philosophy (with some ritual study too). So then I guess the opposite would be everything else? Dunno. I mean, Hsun Tzu does say you should learn your whole life, but then claims the above is all there is to know. Either he is contradicting himself or framing a bare minimum of study. OR that we should study those works our entire lives. Probably the last. Either way, he leaves out the rest of human knowledge, which goes to show how ignorant even a great philosopher can be.

5.) What role do associations with other people play in a good education? Would it be possible to follow Hsun Tzu educational program by reading in isolation?

He makes an important point about the futility of studying (like contemplating) alone. To go in a room for forty-years with a pile of scrolls, and come out “educated,” is impossible. It’s key we speak with others, particularly teachers, who help us understand the material. We also need someone to bounce ideas off of, so here Hsun Tzu is stressing the dialectic (hence the need for these argumentative essays). Learning is a communal affair, and the lone scholar in his ivory tower will get nowhere.

6.) According to Hsun Tzu, what is the ultimate objective of education? What reward can an educated person expect? In your opinion, is this reward a sufficient motivation to pursue learning? Why or why not?

If found this portion of the essay to be one of the most beautiful statements of antiquity, and definitely feel he’s on the mark here. Hsun Tzu claims an educated man simply enjoys being alive more, because he is better equipped to appreciate the wonderful things in life, and avoid the base. But he is also, in an integral sense, his own person. He does not rely or succumb to others, but empowers them. Virtue emanates from the good man, as a wellspring for the rest of society. He does and indeed cannot bow to the weak, the bad, the degenerate. These facets of what it means to be good are both alluring and timeless; I feel the call and seek to emulate the kind of man Hsun Tzu advertizes. It’s difficult, and is not without cons, but I think the old philosopher is correct in his appraisal of education.

1.) What distinction does Hsun Tzu draw between “thought” and “study”? Why does he privilege study over thought in education? How have your teachers emphasized “study” and “thought” differently as you have progressed through school?

The philosopher noticed that he learned far more studying others than he did in isolated contemplation. This is probably an attack on loner intellectuals who became sages by sitting alone and studying the Tao (*COUGH Siddhartha COUGH*), but he also believes it’s simply more effective. We become great by studying great men, not mentally masturbating. Ignoring the patronizing third question I’ll instead retort by positing that a mix of contemplation and study is ideal. You need to first not assume these men are great by default, and review them before you study. And after you study you must expand or improve on what you’ve learned to take it to the next step.

2.) How would you classify Hsun Tzu’s methods of supporting his argument? What kinds of support does he include? What kinds does he omit? How persuasive are his methods?

It’s essay writing, with logical points consistently supporting his thesis. He uses analogies (usually 3-5 at a time) to drive an idea home. He quotes sacred texts, history, and great men. He also repeats his thesis throughout. With the exception of appealing to authority, I find his claims very convincing and favor his style over all other ancient Chinese philosophers.

3.) Several of Hsun Tzu’s metaphors suggest that hard work and study, rather than natural ability, determine success. How is this assertion important to the overall argument? Do you agree with his assessment? Why or why not?

It gives both hope and motivation to his audience. Just because we’re fat lazy slobs doesn’t mean we can’t change, and through study and industry we too can become gentle-sages. I agree deeply, and feel it has become common knowledge today. I mean, there are still missing elements, but the core argument is on point. Widespread education has systematically improved the living standards of every person, society, and state. But even facts aside, I know from my own personal experience that burning Friday-night oil reading this crap has made me happier and a better person.

4.) According to Hsun Tzu, what should be part of the education of a gentleman? What, by implication, should not be part of such an education?

Basically studying laws, classical poetry, history, classical music, and the sages’ philosophy (with some ritual study too). So then I guess the opposite would be everything else? Dunno. I mean, Hsun Tzu does say you should learn your whole life, but then claims the above is all there is to know. Either he is contradicting himself or framing a bare minimum of study. OR that we should study those works our entire lives. Probably the last. Either way, he leaves out the rest of human knowledge, which goes to show how ignorant even a great philosopher can be.

5.) What role do associations with other people play in a good education? Would it be possible to follow Hsun Tzu educational program by reading in isolation?

He makes an important point about the futility of studying (like contemplating) alone. To go in a room for forty-years with a pile of scrolls, and come out “educated,” is impossible. It’s key we speak with others, particularly teachers, who help us understand the material. We also need someone to bounce ideas off of, so here Hsun Tzu is stressing the dialectic (hence the need for these argumentative essays). Learning is a communal affair, and the lone scholar in his ivory tower will get nowhere.

6.) According to Hsun Tzu, what is the ultimate objective of education? What reward can an educated person expect? In your opinion, is this reward a sufficient motivation to pursue learning? Why or why not?

If found this portion of the essay to be one of the most beautiful statements of antiquity, and definitely feel he’s on the mark here. Hsun Tzu claims an educated man simply enjoys being alive more, because he is better equipped to appreciate the wonderful things in life, and avoid the base. But he is also, in an integral sense, his own person. He does not rely or succumb to others, but empowers them. Virtue emanates from the good man, as a wellspring for the rest of society. He does and indeed cannot bow to the weak, the bad, the degenerate. These facets of what it means to be good are both alluring and timeless; I feel the call and seek to emulate the kind of man Hsun Tzu advertizes. It’s difficult, and is not without cons, but I think the old philosopher is correct in his appraisal of education.

Thursday, May 28, 2015

Mencius Versus Hsun Tzu

VERSUS

VERSUS

And here we have another pair of Chinese philosophers who clashed well. Mencius, the greatest Confucian next to the sage himself, and Hsun Tzu, a near-contemporary who ended up influencing the Legalists more than Confucianism, disagreed about a key point regarding human nature: Are people fundamentally good? Or evil?

Mencius: PEOPLE ARE GOOD MAN

1.) What is the rhetorical purpose of the character Kao at the beginning of this section? How does he set up Mencius’ argument? What kinds of objections to his own theory does this device allow Mencius to anticipate?

I have mixed feelings on Kao; he’s basically a vehicle to tactfully elicit Mencius’ thoughts on various issues, which strikes me as vain. On one hand, introducing another character creates a dialogue with back and forth argumentation. Kao does a good job at that, with presenting both opposing and mediated points of view. On the other hand, and this is a criticism of Plato, it essentially strawman’s the opposing argument by having Mencius get the last word. He always wins.

2.) What role does human nature, for Mencius, play in the love we show to our family members? What role does it play in the respect we show to strangers?

It’s simple: our devotion to our family is natural, powerful, and a perfect example of our inborn altruism. So is our kindness to strangers, but because it’s less intense it’s more likely to die if not cultivated. Thus if we cultivate that consideration, it simply becomes an extension to the already existing goodness within us.

3.) A great deal of the debate between Mencius and Kao Tzu concerns the origin of proprietary, or proper social behavior, which is synonymous in the text with “righteousness.” For Kao Tzu, proprietary is a matter of social convention that has nothing to do with human nature. For Mencius, the standards of proprietary are based on qualities that are inherently part of human nature. Which of these views do you find more convincing? Why?

The fundamental question is if we created these traditions as a response to something threatening, or as a natural extension to something inborn. Is it lame to claim both? That we attach purposes to things we do, which are both arbitrary and artificial? But also completely natural to the human condition? I guess the question is making me take a stand, so I’d have to side with Kao here. Even if it an extension it’s still a constructed one, and Mencius cannot claim anything modern man does is natural. But see even this is problematic, as we’ve barely defined “good”, “evil”, and “natural.” Mencius’ definition is sure to be different from mine, but I’ll stick to my guns.

4.) How might Mencius perceive the nature of evil? If human beings are naturally good, where might evil originate?

Mencius believes evil comes from our condition in life, where scarcity of resources or a harsh climate vitalizes evil within us. This is specifically why he advises kings and men alike; kings to provide the condition in the empire for good to flourish, and men so they may endure difficult times. I really like this point, but what about rich brats? People who have everything and are still cruel? Mencius may argue they had bad examples growing up and were not taught correctly, but if our innate goodness is so weak as to die even in affluent environments, then how are his solutions discernible from assuming all people are born evil? And why are some children, even under the same parents, more moral than others? There are definitely holes here.

5.) Do you agree with Mencius’ statement, “Men’s mouths agree in having the same relishes; their ears agree in enjoying the same sounds; their eyes agree in recognizing the same beauty”? How does this idea of conformity, and with it Mencius’ argument, conflict with modern ideas of the individual?

Yes and no. Yes in that humans are fundamentally very similar (we are the same subspecies after all). But no in that we are also each unique, and have different preferences. And this is why the second question is so strong: today we have an issue with any solution that’s ‘one size fits all’. It lacks nuisance and does not contend with the complexity of changing societies. That said, I can’t disagree with Mencius’ principals. Regardless of the innate goodness of humanity, it is certainly wise to design empires that foster kindness through education and adequate living standards.

Hsun Tzu: NAW NIGGA, PEOPLE SUCK

1.) Why does Hsun Tzu repeat his thesis throughout this piece? Does this technique make his argument more effective? What other types of repetition does he use? How does he the repeating images or scenarios to illustrate different aspects of his argument?

It’s something common to the essay genre: it drives the point home. Hsun Tzu repeats a number of points: that he’s countering Mencius, the ‘conscious act’ of the Sages, the need for laws, etc. They do refresh the arguments in your mind, but they can also be tedious and preachy. Meanwhile Mencius’ style is more, well, stylish, and more entertaining. But given our modern sensibilities, Hsun Tzu is more clear.

2.) What distinction does Hsun Tzu draw between ‘nature’ and ‘conscious activity’? Are these categories mutually exclusive? What kinds of things does he place in each category?

His big premise is that evil comes easy, while goodness is hard to attain. Therefore almost anything natural is evil, while conscious activity is when we deviate from our base emotions and act virtuously (to borrow a western word). This seems weak, but Hsun Tzu is focusing on the innate selfishness of organisms, particularly when resources are scarce. Anything that is altruistic goes against this natural selfishness, and is therefore a conscious act. Whether these are mutually exclusive is a good question, but I would actually say they are. Either you are on autopilot, or you think-then-act. If course, you could internalize goodness, in which case that becomes your default.

3.) What does Hsun Tzu see as the origin of ritual principals? How does this differ from Mencius’ view?

The former claims rituals were created by the Sages to suppress humanity’s evil. Mencius claims they are a natural extension of our innate good.

4.) Why does Hsun Tzu assert that “every man who desires to do good does so precisely because his nature is evil”? Do you agree? Are his comparisons to men who are unaccomplished, ugly, camped, poor, and humble valid? Is it possible to desire to be something that is part of one’s nature?

Hsun Tzu is making the insightful point that we wouldn’t struggle so hard to be good if it came easily, or naturally to us. People who want something are generally lacking in it. But the question implies a good counterpoint, that we can indeed want more of a good thing, so to speak. Thus a rich man can want more money, a handsome man can want to be more so, and a good person can certainly strive to be better. But I also think a person is something specifically because they don’t want to be the opposite. A poor man doesn’t care about money, an ugly man is content, and an evil man is perfectly comfortable remaining so. So this would actually entirely negate Hsun Tzu argument by displaying that people only want something when they already have a taste of it.

5.) How does Hsun Tzu define “good” and “evil”? Do his definitions concur with contemporary definitions of the same words?

Yea I had a big problem with his definition. I forgot the exact line, but basically good is anything that does good, and evil is anything that does evil. Other than being a blatant and useless tautology, Hsun Tzu does stress action (and not belief) as the marker. Today we may disagree and point out that just because a person acts ethical, if the action causes more harm than good, then the action was ultimately evil (so ends > means). But to these philosophers we see no such nuance. To simply act well is sufficient, and all will go well. To them the difficulty is in the act itself, and not the integrity of the act. This is where the Greeks are superior to the Chinese, they were more willing to ask the fundamental question: what is good?

6.) How does Hsun Tzu differentiate between capability and possibility? How are they related, and does this inclusion weaken or strengthen the validity of Hsun Tzu’s arguments?

He makes an important distinction that just because a man can do something, doesn’t mean he will. So Mencius’ stressing of the goodness in all men means little if people will never act upon it. This seems like Hsun Tzu is giving ground, but really he’s countering Mencius from another angle. Even if the latter is correct, his philosophy is still impractical. It’s safer to assume all men are evil and will probably not act upon their capabilities.

7.) According to Hsun Tzu, what role does environment play in how humans deal with their nature? What kind of environmental factors determine a person’s inclination or rejection of human nature?

Hsun Tzu believes environment is everything (he repeats this statement twice at his essay’s close). If people grow in a good environment they will have the tools to defy their evil nature. If in a bad environment they will give in to it. The main elements, strangely similar to Mencius’ opinion, is education and living standards. A man needs these to be good.

Mencius versus Hsun Tzu

1.) Mencius and Hsun Tzu disagree completely about human nature, yet both are dedicated Confucians. What elements of their respective philosophies justify their inclusion as members of the same school of thought?

They both stress the same things: ritual observance, relationship of man to the state, and an ethical imperative in living life. Interestingly, Hsun Tzu ended up influencing the legalists more, while Mencius became the most celebrated Confucian next to the great Sage himself. That’s because, while the practical effect of their arguments were so similar, Hsun Tzu was ultimately more heavy handed, and Mencius more trusting in humanity.

2.) How does Hsun Tzu’s writing style compare to Mencius’? Are his rhetorical strategies more or less effective than those of his major philosophical opponent? Why?

The former is an essay writer and the latter a more conventional Chinese writer, utilizing epigramic dialogues. These both have pros and cons; Hsun Tzu is clearer and more convincing while Mencius is more enjoyable and thought-provoking. Gonna stick to me modern sensibilities, however, and go with Hsun.

3.) Who was right? Is man fundamentally good, or evil?

Brass tacks. I mean, these two did a way better job at tackling the issue than I thought possible given the era. (Goes to show my ignorance at the sophistication of the Chinese.) Both make a few powerful points: Mencius is right to point out our natural inclination to help others with no gain to ourselves, and our propensity for self-sacrifice, as well as our natural enjoyment of good, and innate disgust at evil. But Hsun Tzu is right to highlight how these may be built up by society, and without it we are prone to selfishness and cruelty. I really don’t know. I don’t want to say it’s a dice roll for each person at birth, both our natural inclinations and environmental build-up. I think goodness certainly survives while evil dies. But good also seems to build upon the foundation of evil. And besides these terms often seem impotent; is anything truly good or truly evil? Now I’m just getting tedious, so let me close by saying I’m open to both and am eager to see where the argument evolves from here.

Sunday, May 10, 2015

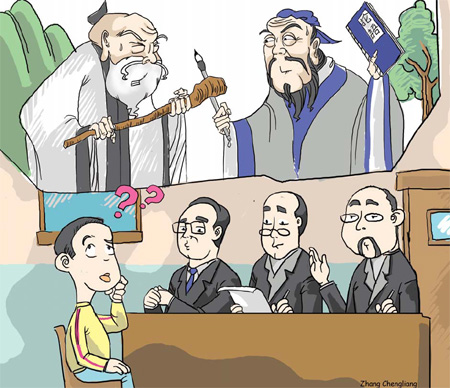

Mozi versus Sun Tzu

VERSUS

VERSUS

It seems to be an irony of history that periods of intense warfare produce intense climates of mental thought. Not only in art, but philosophy and science too. A prime example is the Warring States Period of Ancient China (475-221 BCE), where 8 states of the old Zhou dynasty fought for supremacy. Before and during this period of incessant combat many philosophies sprung up trying to image the best way to resolve the war, bring peace to the people, create a stable government, and ensure future prosperity. The Chinese joked that a hundred schools of thought manifested during this time, and they weren’t that far off. Posterity has rewarded a lucky few, namely Confucianism and Daoism, but many fascinating and intelligent world-views have faded into time. One I’d like to resurrect today is Mohism, from the great Mozi (470-391 BCE), who was a popular radical in early China. He argued for the concept of universal love, to all human beings and all creatures. He was also an extreme pragmatist. This put him starkly at odds with the Confucists, who believed that some relationships were more significant than others (therefore you can’t love everyone equally) and paid strict observance to ritual (which Mozi said was unpractical and useless).

But I don’t want to clash Mozi with Confucius, rather instead another influential theorist who didn’t author a school of thought at all: Sun-Tzu. In my review of the Art of War I noted how 99% of the work was rather useless, excepting four poignant points that deserve attention: war as the greatest responsibility of the state, the general’s right to disobey the emperor, the emperor’s ethical imperative to avoid or quickly win any battle, and the advantage of the spy over infantry. I think it’ll be fruitful to compare these claims with Mozi who was fiercely anti-war. Let me first analyze them separately and then compare.

Mozi

What comparisons did Mo Tzu use to illustrate the immortality of war? Are these comparisons valid? Are they effective in presenting his argument?

Mozi uses simple allegories to illustrate how in everyday society we take offense at minor and major crimes, and enact punishment on the perpetrator. But when a country commits atrocities we not only turn a blind eye but sometimes celebrate them as ‘righteous’. For example, if a man steals an apple he is a thief, but if a country steals land for agriculture it is labeled as a strong conqueror. To ask whether this is a valid comparison is a good question, and depends on how you view morality. If it is something objective, or ideal, then I don’t think offensive war can be justified. But if morality is utilitarian, then it would depend on the ends. A poor man taking an apple to feed his family isn’t all that bad, just as a country waging war to feed its people is more forgivable. This gets real messy when a country starts waging battles for ancestral land or pre-emptive strikes, but Mozi doesn’t consider or care about these scenarios. His arguments are certainly persuasive given the limits he imposes on war’s aim, but unfortunately there is more nuance here.

The real surprise to me is the complete disregard for the Mandate of Heaven. I’m not sure how he felt about the concept, but my understanding is that any conquest must be approved by Heaven, no? So to call war evil is to ignore a very important theological belief in Chinese history.

What is the moral imperative at the heart of all the actions, including war, that Mo Tzu considers evil? Can his position be reduced to a “golden rule” of appropriate behavior?

It seems Mozi ultimately condemns actions that benefit yourself at the cost of others. This certainly seems like ‘golden rule’ material to me, but what about institutions that act as a middle man? Such as gambling? Or zero-sum economies? Maybe I’m over thinking it, but his rule seems against all competition. Mozi may in fact be an early advocate of socialist economies and equal education. But I run the risk of putting words in his mouth. I know from another piece he argues against entertainment on the grounds it distracts from constructive action, so it seems anything that depletes a moral imperative is degenerate to him.

What is the point of Mo Tzu’s discussion of black and white? What is he saying about human perceptions of scale?

I liked this part, as Mozi simultaneously refutes and

attacks dichotomies of judgment. He mentions how men can judge something when

it is local or easily digestible, but when it becomes abstract or mentally overwhelming,

their judgment becomes inconsistent and they cling to extremes instead of

recognizing nuance, or even simplicity. Microcosms don’t necessarily change

when enlarged. The conclusion is that a man cannot be said to have a strong

ethical stance if it is inconsistent or limited in scope. Mozi argues these

peoples’ opinions should be disregarded as a result.

What does Mo Tzu mean by “offensive warfare”? What do you think he would say about defensive warfare? What conditions does he suggest have to be present to make war immoral?

I think he obviously means war that is meant to take from others for one’s own benefit, similar to his standards for the individual. I assume he would approve a defensive war, as long as it doesn’t grow to be something more. I feel uncomfortable answering the last question as it denies Mozi the right to clarify, but seeing as he’s dead let me have a go: a war is immoral if a country acts based off ‘wants’ and not ‘needs’, like an individual. I can’t say I agree, but I don’t entirely disagree either. This holds the same standards for people as it does states, which is admirable and possibly correct, but doesn’t reflect reality in the least.

Sun Tzu

Why does Sun Tzu structure his advice on war as a series of short epigrams with no expansion or development? What is the rhetorical effect of this structure? Is it more or less effective than a traditional essay format?

What a great question. My guess is that epigrams are frankly more authoritative; instead of proving something you simply state facts with the weight of your experience behind them. I also think they’re more thought provoking, as instead of expending effort being persuaded you spend your time thinking about the statements themselves, which lack more context than a well-reasoned essay. This can also be a con though as it’s less clear, but Sun Tzu may want to encourage creative thinking over placid acceptance.

What does “subdue the enemy without fighting” mean? How is it possible to achieve victory without conflict? Why would a peaceful victory be considered superior to winning an armed conflict?

A beautiful line by Sun Tzu; the statement calls for winning an objective without resorting to violence. The fact is war is simply a means to an end (whether that end is more land, more money, etc.), and it’s more humane to first try and achieve that end without killing people, which should always be avoided if possible. You’re certainly able to achieve victory without conflict through diplomacy, trade, or bribes. The reason peaceful victory is preferable is that it saves human lives, which is self-explanatory. The only advantage to armed conflict is that it’s sometimes easier/quicker, but even that’s debatable.

Why did Sun Tzu hold that “the worst policy is to attack cities”?

Frankly, because the ancient Chinese didn’t have good siege weapons. In Sun Tzu’s time sieging was a huge waste of time, lives, and resources, and it was more effective attacking other objectives. Again the general is concerned with efficient action and saving lives.

Why does Sun Tzu place such great importance on a commander’s self-knowledge? How is self-knowledge important beyond the scope of military conflict? What kinds of mistakes can be made by people who do not really understand themselves?

It’s because a commander should know what they’re strong and what they’re weak at. If a general goes with a strategy he has little experience or affinity for, it can be a disaster, but it would be much wiser to take the option that best fits his abilities. This is good advice outside of warfare too, as we should always know our strengths and weakness to better navigate life.

Can Sun Tzu’s philosophy of war be applied beyond the scope of military affairs? Do any of his aphorisms seem relevant to other kinds of human conflict? Why has The Art of War become a best seller among American business professionals?

The general philosophy and some of his aphorisms, sure. A lot of the AoW is specific only to ancient Chinese warfare, but some of it, particularly his principals and modes of attack, are timeless and good advice for many of life’s conflicts. This is specifically why American businesses, especially in the 1980s, clung to the work. I would say the most useful advice is to understand that a.) Objectives, even when blocked by conflict, need not be unethical. It’s just as important to be humane as it is efficient. And b.) War, as with anything in life, deserves serious study and reflection.

Who Wins?

Compare Sun Tzu’s view of war with that of his contemporary Mo Tzu. Why do you think Mo Tzu writes exclusively about the morality of war while Sun Tzu refuses even to address the question?

I would say the difference is that Sun Tzu accepts the reality of war while Mozi believes it need not be a given. Mozi feels that if people, who honestly try to be good, held their country under the same moral standards they live by, there would be less war and more peace. Sun Tzu perhaps isn’t as optimistic, or rather feels given the inevitability of conflict, it would be more useful to instruct commanders on appropriate action during warfare. This though is also optimistic, as it assumes people will consider these options and not just carelessly spend lives with what’s most convenient.

I can’t easily say who I agree with more. Sun Tzu appears sexier, as he attempts to channel an evil into something more ethical. But Mozi grapples the issue and doesn’t let go: a country and citizenry must all be equally held accountable for their actions. For criticisms, Sun Tzu still dodges the question, and Mozi doesn’t articulate his definition of a just war. That said, the two provide an important debate about conflict that doesn’t exist anywhere else on a world ripe with strife.

What does Mo Tzu mean by “offensive warfare”? What do you think he would say about defensive warfare? What conditions does he suggest have to be present to make war immoral?

I think he obviously means war that is meant to take from others for one’s own benefit, similar to his standards for the individual. I assume he would approve a defensive war, as long as it doesn’t grow to be something more. I feel uncomfortable answering the last question as it denies Mozi the right to clarify, but seeing as he’s dead let me have a go: a war is immoral if a country acts based off ‘wants’ and not ‘needs’, like an individual. I can’t say I agree, but I don’t entirely disagree either. This holds the same standards for people as it does states, which is admirable and possibly correct, but doesn’t reflect reality in the least.

Sun Tzu

Why does Sun Tzu structure his advice on war as a series of short epigrams with no expansion or development? What is the rhetorical effect of this structure? Is it more or less effective than a traditional essay format?

What a great question. My guess is that epigrams are frankly more authoritative; instead of proving something you simply state facts with the weight of your experience behind them. I also think they’re more thought provoking, as instead of expending effort being persuaded you spend your time thinking about the statements themselves, which lack more context than a well-reasoned essay. This can also be a con though as it’s less clear, but Sun Tzu may want to encourage creative thinking over placid acceptance.

What does “subdue the enemy without fighting” mean? How is it possible to achieve victory without conflict? Why would a peaceful victory be considered superior to winning an armed conflict?

A beautiful line by Sun Tzu; the statement calls for winning an objective without resorting to violence. The fact is war is simply a means to an end (whether that end is more land, more money, etc.), and it’s more humane to first try and achieve that end without killing people, which should always be avoided if possible. You’re certainly able to achieve victory without conflict through diplomacy, trade, or bribes. The reason peaceful victory is preferable is that it saves human lives, which is self-explanatory. The only advantage to armed conflict is that it’s sometimes easier/quicker, but even that’s debatable.

Why did Sun Tzu hold that “the worst policy is to attack cities”?

Frankly, because the ancient Chinese didn’t have good siege weapons. In Sun Tzu’s time sieging was a huge waste of time, lives, and resources, and it was more effective attacking other objectives. Again the general is concerned with efficient action and saving lives.

Why does Sun Tzu place such great importance on a commander’s self-knowledge? How is self-knowledge important beyond the scope of military conflict? What kinds of mistakes can be made by people who do not really understand themselves?

It’s because a commander should know what they’re strong and what they’re weak at. If a general goes with a strategy he has little experience or affinity for, it can be a disaster, but it would be much wiser to take the option that best fits his abilities. This is good advice outside of warfare too, as we should always know our strengths and weakness to better navigate life.

Can Sun Tzu’s philosophy of war be applied beyond the scope of military affairs? Do any of his aphorisms seem relevant to other kinds of human conflict? Why has The Art of War become a best seller among American business professionals?

The general philosophy and some of his aphorisms, sure. A lot of the AoW is specific only to ancient Chinese warfare, but some of it, particularly his principals and modes of attack, are timeless and good advice for many of life’s conflicts. This is specifically why American businesses, especially in the 1980s, clung to the work. I would say the most useful advice is to understand that a.) Objectives, even when blocked by conflict, need not be unethical. It’s just as important to be humane as it is efficient. And b.) War, as with anything in life, deserves serious study and reflection.

Who Wins?

Compare Sun Tzu’s view of war with that of his contemporary Mo Tzu. Why do you think Mo Tzu writes exclusively about the morality of war while Sun Tzu refuses even to address the question?

I would say the difference is that Sun Tzu accepts the reality of war while Mozi believes it need not be a given. Mozi feels that if people, who honestly try to be good, held their country under the same moral standards they live by, there would be less war and more peace. Sun Tzu perhaps isn’t as optimistic, or rather feels given the inevitability of conflict, it would be more useful to instruct commanders on appropriate action during warfare. This though is also optimistic, as it assumes people will consider these options and not just carelessly spend lives with what’s most convenient.

I can’t easily say who I agree with more. Sun Tzu appears sexier, as he attempts to channel an evil into something more ethical. But Mozi grapples the issue and doesn’t let go: a country and citizenry must all be equally held accountable for their actions. For criticisms, Sun Tzu still dodges the question, and Mozi doesn’t articulate his definition of a just war. That said, the two provide an important debate about conflict that doesn’t exist anywhere else on a world ripe with strife.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)